February’s Fungi Focus: Antrodia carbonica

There is an aspect to going out on a fungi foray, and indeed looking at all parts of the natural world (I’m sure insect hunters will tell you the same), that makes one think of ‘Pokémon Go’. You head out into the woods, not knowing what you’ll find, but with the awareness that some of your discoveries definitively trump others in terms of their impressiveness and rarity. Of course, not everything that is rare is particularly impressive to look at, but that doesn’t dampen the excitement when you realise you have found something that has been very seldom recorded and which you might have been the only person ever to notice in your area. Many crust fungi can be considered rare precisely because they are so rarely recorded. Part of the reason they are so rarely recorded is because they are so rarely identified, and part of the reason they are so rarely identified is because, on the surface, many appear as relatively nondescript compared with more flamboyant members of their kingdom. You have to look long and carefully, often through a microscope, to work out what they are.

As I’ve mentioned in a number of these postings – for example, in last year’s focus on the various resupinate fungi bearing the work ‘porecrust’ in their common names – it is precisely this sort of wallflower anonymity that appeals to me about the crusts and bracket fungi. It is much easier to discover new and exciting things and to uncover the secrets of your local area in places where no one else is looking.

It was over six months ago now, about a week into August, when I was strolling around my local woods in what seemed like a futile hunt for fungi to photograph. About half an hour into my foray, it began to drizzle, so I started wending my way back home, slightly crestfallen that I’d not really found anything of interest. The rain quickly got heavier, and then it truly started hammering it down so, clad in just T-shirt and shorts, I threw myself beneath a heavy patch of tree cover at the edge of the path to escape from the deluge. It was here that I glimpsed something out of the corner of my eye in a tiny grove just the other side of the trees I was sheltering under – a small patch of white growing on a rotten tree stump.

I immediately spotted that it was some form of resupinate, or crust fungus, notoriously difficult to identify and really the domain of the more obsessive fungi fans. Well, I moved in closer to take a closer look and realised it had pores that were facing downwards from big shelf-like vertical outgrowths that gave the whole structure the semblance of an iceberg. I’d seen something like it before while flicking through my books, and the genus name of Antrodia sprang to my mind.

So I cut off a thin slither to take a spore print from and inspect under the microscope, and once I’d arrived back at the house, soaked to the skin, I grabbed my copy of the ‘Resupinates of Hampshire’ book off the shelf to look for likely candidates. Antrodia xantha, or the Yellow Porecrust, seemed the closest fit, save for the fact that it wasn’t that yellow. Fair enough, I thought, the yellowing came with age, and this seemed like a pretty fresh growth. But then I looked at the spores under the microscope, and they were clearly much larger.

There was one other candidate listed in the book, which was a species described as “very rare” called Antrodia carbonica. In fact, so rare is it that a quick internet scour revealed very few recorded findings of this in the UK. It couldn’t be, could it?

Indeed, checking on CATE [Fungus Conservation Trust database], the only record for this species was from September 2015, in Hampshire, and on Pseudotsuga menziesii, better known to you and I as the Douglas Fir. Presumably this record was added by the authors of ‘Resupinates of Hampshire’, which mentioned that this Antrodia species has been found exclusively on the stumps of Douglas Firs. Now I have enough difficulty identifying trees when they have leaves on them, but despite this being a predominantly mixed deciduous woodland, the reason I ended up in the particular spot was to shelter from the rain in an area where there was an abundance of holly and a large conifer of some sort right next to this stump where I found it.

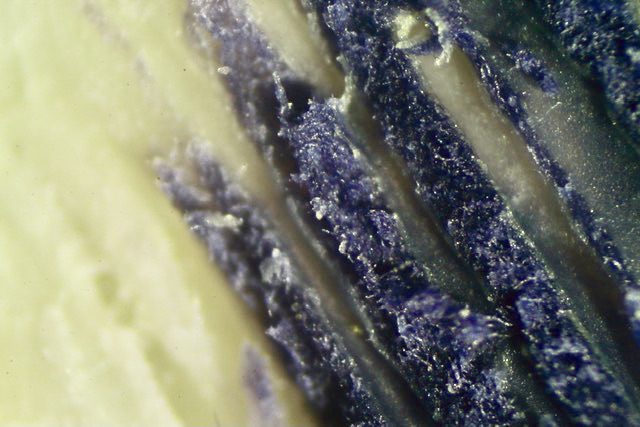

The other key feature of this particular species was that if you apply a drop of Meltzer's Reagent to it, the flesh stains from its ivory white to a blueish colour. One should never underestimate the use of chemical testing when it comes to zeroing in on an identification.

Cinnamon Bracket Hapalopilus nidulans

Take, for example, the Cinnamon Bracket (Hapalopilus nidulans), which is a fairly unremarkable light brown colour until one adds a drop of KOH (or potassium hydroxide) solution, and the area you’ve applied it to turns a dramatic violet colour (see image above). Well, I did the chemical test on my new find, and sure enough, it turned blackish-blue as described.

Staining blue black under Meltzer's Ragent is a unique feature of Antrodia carbonica

This was getting exciting, so after mentioning my findings on a couple of mycological Facebook groups and being met with a degree of scepticism, I contacted Paul Hugill, one of the authors of ‘Resupinates of Hampshire’, asking if he would be interested in taking a look. I turns out he was, and so off to the Post Office I trotted and dispatched a piece I’d returned later to cut from the fungus and waited patiently. Many weeks passed, then I finally decided to chase Paul Hugill up once more and thus the confirmation came through – that I’d made one of the few recorded findings of Antrodia carbonica in the UK! Over the following months, I came to realise that none of this was as exciting to anyone else in my social circles as it was for me.

However, one of the reasons I am making Antrodia carbonica the subject of this month’s fungi focus is that this large chunky fruit body is still there where I left, albeit a little tarnished and worn, and serves as a focal point that I gravitate towards on many of my regular woodlands excursions, as the location seems to be a bit of a hotspot for other finds too. This in itself serves to highlight that crust fungi can be found far longer throughout the year than many other species, which appear for a mere matter of days.

The other reason to focus on this species is because it makes one wonder about how certain individual fungi get to be found in certain spots. Why, for example, was this one Douglas Fir stump found in a predominantly broadleaf woodlands common area, next to a very well-trodden path, literally a hundred metres from my front door on the outskirts of Bromley? How did the tree get there, when did it get there, and how old was it when it became what to most people (but not to its fungal inhabitant) would appear to be nothing more than a rotting stump?

The other reason to focus on this species is because it makes one wonder about how certain individual fungi get to be found in certain spots. Why, for example, was this one Douglas Fir stump found in a predominantly broadleaf woodlands common area, next to a very well-trodden path, literally a hundred metres from my front door on the outskirts of Bromley? How did the tree get there, when did it get there, and how old was it when it became what to most people (but not to its fungal inhabitant) would appear to be nothing more than a rotting stump?

Did this Antrodia carbonica species arrive on the tree as a young sapling planted in this area, or did the spores make it over on the wind from elsewhere much later to miraculously arrive on the only substrate capable of hosting it? Or are there many more examples of this species lingering in Douglas Fir stumps across the country that have yet to manifest themselves by developing fruit bodies? Or are the developed fruit bodies sitting there hidden in plain sight, passed by unnoticed? These questions are perhaps more seductive to me because I know I am the only person who has stood by this particular rotten tree stump and pondered upon the mysteries unveiled by this particular discovery.

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

Not sure if I’ve found Antrodia Carbonica in the Peak District. Have taken photos.

That’s interesting Regina. This piece of common land where I discovered the Antrodia specimen used to be part made up of a number of privately owned estates that was given back for public usage in the 1860s, I believe. It’s mixed woodlands with a lot of non-natives like rhododendrons, but also worth noting that nearby there is a Christmas tree farm. Perhaps it’s not surprising that douglas firs have been able to grow there, but as you say, how individual fungi species manage to find their hosts is indeed a bigger and more interesting question.

Hi there,

Interesting about the Doug-firs. I live near the Olympic Mountains in Washington State USA, which is basically ground zero for Dougies, as we call them. Not only are they far and away the most common tree around, but they also host both a wide diversity and great abundance of wood-rotting fungi, well beyond any of the other native species of trees. Often they are the only trees I find anything on. Hemlocks and bigleaf maples are distant seconds and thirds for finding polypores or crusts. Doug-firs do reseed prolifically here but of course they would, being native and widespread. The seeds can float quite a ways although they are short lived. How fungi travel to find the Dougies planted outside of their natural range, would be a very interesting question to investigate.

Dear Jasper,

Congratulations for your text on A. carbonica.I created the genus Lentoporia for this species (see on my web site under): Mushrooms nomenclatural novelties no. 5.

Also, you can see my phylotree below on my website.https://sergeaudetmyco.com/antrodia/

I continue my research on this species and I need to know if there have strands or rhizomorphs in decay under this species.

Thank you in advance.

Serge Audet

Dear Jasper,

My genus Lentoporia for your species is confirmed in the paper below:

Liu, S., Chen, YY., Sun, YF. et al. Systematic classification and phylogenetic relationships of the brown-rot fungi within the Polyporales. Fungal Diversity 118, 1–94 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-022-00511-2

Very best.

Serge Audet

Serge Audet

24 March, 2023