July Fungi Focus : Fairy Inkcap (Coprinellus disseminatus)

Weather-wise, it’s been a bit all over the place this Summer. However, the hotter spells punctuated by heavy downpours that characterise July, along with the dense leaf canopy of our broadleaf woodland areas at this time of year, have resulted in an at times oppressive humidity that seems particularly conducive to the first blooms of our more familiar cap-and-stem types of mushrooms and toadstools, marking a turning point that will take us within a couple of months to a period where our wooded areas will soon be flooded with fungi. Annoyingly, the summer months similarly see our woodlands buzzing with all manner of flying and biting insects, making it less tempting to head out and find and photograph the species more prevalent in this early period of mycological bounty!

Fairy Inkcaps growing on a rotten tree stump.

Nevertheless, our rather temperamental weather conditions of late have thus far made 2021 a rather good year for mushroom hunters. I’ve found a large number of chanterelles, agarics and russulas, (the colourfully capped mycorrhizal species known commonly as brittlegills) over the past month. In tune with the seasons, marasmius species such as the delicate Collared Parachute and other thin-fleshed leaf litter-inhabiting types prevalent in the summer, like the Pale Brittlestem (Psathyrella candolleana) are also popping all over the forest floor. Outside of the strict domain of fungi, slime moulds appear to be having a field day, in a way I have seldom witnessed before.

This month’s focus is on another easily-recognisable seasonal stalwart that has been with us since Spring and will remain with us well into Winter, the Fairy Inkcap (Coprinellus disseminatus). These look very much like the various species of mycena or bonnet fungi that often cause huge headaches when trying to identify them, and although not part of this group, one of their alternate names, Fairies Bonnets, highlights certain shared physical features.

There's a slight yellowish tinge to the grey caps of the Fairy Inkcap

They have very small egg, bell or bonnet-shaped caps, averaging around 1cm in diameter, which range from an early white colour upon their first emergence then darken through various shades of grey with a yellowish tinge, blackening from the outside inwards as they age. The caps are pleated with a thin grooves on top radiating outwards from the centre, and if caught at the right time, when looked at under a hand lens, they are covered with a fine down of small projecting hairs. The stipe (stem) is white, thin, hollow and easily snapped.

Perhaps their closest common lookalike is the Glistening or Mica Inkcap (Coprinellus micaceus), another species found in dark damp places growing on and around rotten stumps and logs in “mull” soils rich in organic matter, often in places like parks and gardens. Both belong to the group known as the coprinoids: saprobic fungi that derive nourishment from dead or decaying plant material, which they assist in breaking down, be it wood, leaf litter, dung or other debris.

The picturesque Coprinopsis picacea, or Magpie Inkcap, is found on forest litter or bark chips in woodlands, for example. The majestic Shaggy Inkcap, or Lawyer’s Wig (Coprinus comatus) is found on disturbed soil in more grassy areas, such as roadside verges, and new lawns. The delicate Snowy Inkcap (Coprinopsis nivea) is again found in grassland areas, but growing on horse or cow dung and other types of manure. You might have seen some of the more fly-by-night coprinoids like the Diaphanous Inkcap (Coprinopsis ephemeroides) growing and quickly disappearing again from plant pot compost. The Firerug Inkcap (Coprinellus domesticus), whose substrate is decaying hardwood, also makes incursions into the domestic space, as it’s latin name indicates, appearing in suitable places in dank cellars and rotting rafters.

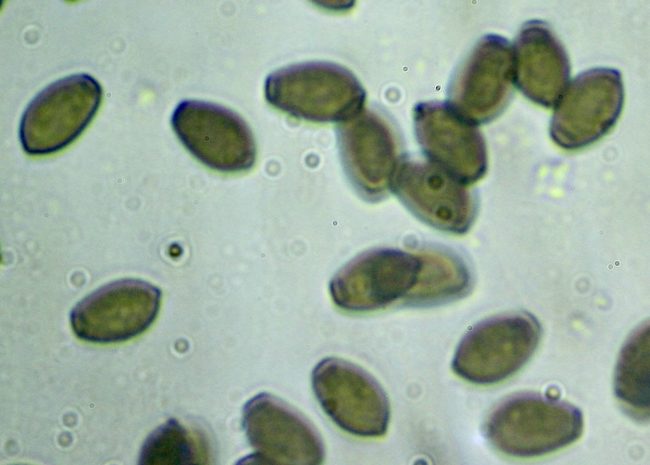

Black spores (lay a cap down on a piece of paper for a couple of hours to check), which turn the gills black from the edges inwards as they mature within them, define the coprinoids, as does their habit of the gills and caps melting as the spores develop. Such deliquescence into inky black ooze is what gives the inkscap their common names. It is not, however, a feature of the Fairy Inkcap, which for this reason is somewhat unusual within this group. Rather than melt into mush, the caps of the Fairy Inkcap remain brittle, and easily teared, hence their alternate common name of Trooping Crumble Cap.

A troop of Fairy Inkcaps, a mushroom that occurs in vast numbers

The “trooping part” is down to these mushrooms occurring in vast swathes that spread out allow over the place. Though tiny in their own right, their overall appearance en masse is very impressive and not likely to be missed. Glistening Inkcaps, by contrast, are not only much larger (about 2-4cm diameter against the 5-15mm of the Fairy Inkcaps), but tend to grow in clumps and clusters. And then there’s there other tell-tale sign highlighted in the name of this latter type – their caps tend to be covered in granular specks that catch the light. (And before the question pops into anyone’s heads, neither can be considered worthwhile edibles).

With all this in mind, Fairy Inkcaps are pretty easy to distinguish for beginners, and certainly the large numbers in which they appear make this dainty mushroom one that is unlikely to be missed.

Fairy Inkcap spores appear black, like other copriniods, are ovoid and have a small germ pore, the hole visible at one of the ends.

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

Great article! We’ve actually got some fairy inkcaps that have started growing out of our indoor plant pot. Which was a huge surprise. The plant it an Elephant Ear plant.

Just found them in Mocketts. Thanks for the ident

Karen McKenzie

8 June, 2022