September’s Fungi Focus: Boletes and the Bolete Eater (Hypomyces chrysospermus)

It wouldn’t be too bold to suggest that the main lure into the mystical world of mycology for many is the promise of finding something tasty to eat. However, my own reckoning is that a large proportion of would-be wild food gourmands soon move on to pastures new after discovering that the number of commonly found fungi that are actually edible, readily identifiable or even particularly tasty is relatively low.

Moreover, as those who do know what they are looking for soon discover, you have to get out there pretty early and possess particularly keen eyes to stay ahead of the competition - be this from the new generation of food-for-free fanatics whose heads have been turned ground-wards over the past decade or so by TV foragers such as Ray Mears or Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall, or from those members of the woodland ecosystem more reliant on the fruits of the forest, such as squirrels, slugs, grubs, bugs and, yes, even other fungi.

Questions of edibility have not really been the purpose of these Fungi Focus (formerly Monthly Mushroom) posts anyway. Instead I have mainly tried to point towards a whole hidden world of interest beyond the culinary. This is not to say that if I did chance upon a plump Penny Bun, however…...

A pristine pair of Porcini, or Penny Buns

Yes, we are entering into the mushroom season good and proper now, and among the first heralds of Autumn are the various boletes of which the aforementioned Boletus edulis, a.k.a. the cep, porcini or King Bolete, is amongst the most prized. Just like your more recognisable edible cap-and-stem types such as the common field mushrooms, the boletes are basidiomycetes, but instead of gills, their underside consists of a spongy mass covered in pores from which spores are released.

You would think these pored undersides would be enough to keep them categorised as a separate group in their own right, and for many moons they were treated as such, but new genetic methods of classification have shown different family groupings. This is reflected in their Latin names, many of which have been re-assigned even quite recently. And so the Suede Bolete, once known scientifically as Boletus subtomentosus, has now been renamed Xerocomus subtomentosus. The Red Cracking Bolete, formerly Boletus chrysenteron, has become Xerocomellus chrysenteron, while the one-time Boletus castaneus, or the Chestnut Bolete, is Gyroporus castaneus.

The white pores that turn yellow of the Chestnut Bolete are the keys to its identification

It is all very confusing for those of us who don’t want to delve too far into the mysterious taxonomic minutiae of mushrooms, but most common field guides keep things simple and stick with the old binomials, and anyway, one can always just fall back on the English common names of the more prolific types.

What is surprising is that some species categorised under the generic term boletes are actually more closely related to gilled mushrooms than they are to other boletes. Others are closer to the gasteroid fungi types like Earthballs. In some ways this makes sense. Where one finds Earthballs, one often finds boletes – and there is indeed one notorious type, the Parasitic Bolete (Pseudoboletus parasiticus), that actually only grows on Earthballs themselves (or at least, it grows on, from or with Earthballs – it is not exactly clear which the case may be). After all, boletes and Earthballs mycorrhizal species, meaning that they form mutually beneficially relationships with trees in the same way as the agaric species discussed in a previous post on Fly Agarics. In other words, boletes, Earthballs and agarics, as well as many other species such as the colourful brittlegills of the Russula genus (to be covered next month), associate with different host trees, gaining energy from the sugars secreted by the roots in return for the various mineral compounds they in turn draw from the soil to give back to the trees.

Common Earthball parasitised by a Parasitic Bolete that in turn is playing host to an unidentifiable fungal mould demonstrating the inter-relations of the fungi kingdom

It is for this reason that many of the various species described as boletes, as well as the other mentioned mycorrhizal types, begin appearing in mid-to-late Summer, when the earth might otherwise be bone dry. This is because they have access to reserves of moisture deeper below ground surface due to their association with tree roots. This need for a host tree is also the reason why things like Penny Buns are considerably more difficult to cultivate commercially than saprobic types like our common button mushrooms (which get all the nutrients they need by breaking down already well-rotted manure or compost).

Chestnut bolete (Gyroporus castaneus)

All of which makes the Penny Bun a very welcome find. However, Penny Buns are not the only types of boletes and, as detailed above, are not necessarily that closely related to the numerous other mushrooms with pores instead of gills. In other words, pores should not be the be all and all of identification. A few of these pored fungi are poisonous. One heuristic is that if the flesh bruises a blue colour and any part of it is lurid red, you will definitely want to avoid it, as it could well be something nasty like the aptly-named Devil’s Bolete (Rubroboletus satanas, previously just simply Boletus satanas) or the Deceiving Bolete (Suillellus queletii, formerly Boletus queletii). But as I already mentioned, discussions of edibility aren’t the focus here, so if you want to go down that route, you can look at articles like ‘Identifying Boletus Mushrooms’ on Wild Food UK and blame them if you get very sick.

The Ghost Bolete

To be honest, despite the existence of more obvious species like the Ghost Bolete (Leccinum holopus), the only all-white one as far as I am aware, or the poisonous Slippery Jack (Suillus luteus), with its slimy cap and a ring around the stem similar to the agarics, I find boletes a bit of a challenge to identify accurately. However, there is one website dedicated to them : https://boletales.com and Geoffrey Kibby has published a book, British Boletes, with a key to 80 or so species found in the British Isles.

The biggest problem in identification is that pristine specimens are so rare. Most boletus seem particularly prone to the kind of entomological or vermicular collateral damage that quickly renders them unidentifiable, yet alone edible. The spongy mass containing the pores quickly change colour with age, mostly to a sickly ochre or green colour, while slugs, worms, maggots or whatever all seem to take great delight in reducing these majestic fruitbodies to a slimy pulp.

Hypomyces chrysospermus making a meal out of an unidentified bolete

At least one such agent of attrition is itself fungal in nature. This is Hypomyces chrysospermus, which manifests itself initially as a white mould-like flush that soon turns a lurid yellow. It’s exclusive taste for its host leads to the obvious common name given by the British Mycological Society of Bolete Mould, although many people now seem to refer to it by the much more poetic moniker of the Bolete Eater.

There are a number of different species in the Hypomyces genus of parasitic types that feed off the fruiting bodies of other mushrooms, crusts or brackets. Their common names reflect the colours and individual tastes: for example, there’s the Pink Polypore Mould (Hypomyces rosellus), which manifests itself as pinkish scarlet dots that spread like measles across the spore-producing surface of polyporous crust and bracket fungi, and the delightfully named Green gillgobbler (Hypomyces viridis). Curiously, there is at least one Hypomyces that is edible, or rather, it transforms many an otherwise ordinary mushroom into something more epicurean. This is Hypomyces lactifluorum, the so-called Lobster fungus, so named due to the red colour and subtle bouquet it lends to its host mushrooms. I have tried this, bought from a market in Quebec, and presumably cultivated, as this really isn’t one that you’d think of going hunting for oneself.

The Bolete Eater goes for the underside of the cap first

Hypomyces chrysospermus lends an altogether more overwhelmingly fishy stench to the boletes it grows upon, and I doubt there would be anyone desperate enough to entertain the thought of putting it anywhere near their mouth, not least because whatever type of bolete it is growing upon rapidly becomes unidentifiable as this secondary fungal growth rots it down.

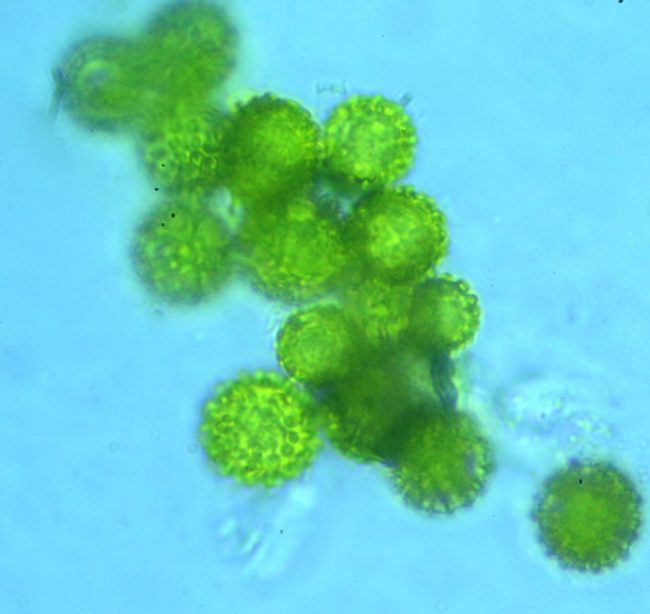

I probably wouldn’t have bothered making the Bolete Eater the subject of September’s Fungi Focus were it not for the fact it looks much more interesting under a microscope. Basically the visible presence of this rather odd fungi is almost entirely due to its spores. In its initial white fluffy stage, these are elliptical and smooth and between 10-30 microns in length (0.01-0.03mm) and 5-12 wide. The lurid yellow powdery coating that develops on this initially covering is made up of its asexual spores, which are spherical, spiny and range up to 25 microns (or 0.025mm) in diameter. There is then a third phase, that I have not been able to see for myself because by this point the host bolete has usually pretty much deliquesced into a revolting smelling slime, which reveals that Hypomyces chrysospermus is in fact an ascomycete fungi, producing a third type of sexual spores in batches of eight in long sacs. In this final stage the spores are once more elliptical and 30 microns long, but a lot narrower, only reaching up to 6 microns in width, and also possess a separating wall in the cell.

The warted yellow asexual spores of Hypomyces chrysospermus in its second phase

Depending on the state of decay of the bolete host and the Bolete Eater’s various stages of development, all three spores can exist simultaneously (and therefore be visible under a microscope at the same time).

I have no idea why this strange fungus has three different types of spores across its reproductive cycle, rather like the rust fungi. Fungi sexuality is rather a mysterious matter. However, what the various Hypomyces do demonstrate, just like the example of the obscure microscopic Mollisina oedema that grows upon the Blackberry Leaf Rust detailed last month, is that there are a range of cross-species relationships within the fungi kingdom that few really understand, pointing to the wider implications of our limited comprehension of the interconnectedness of nature.

Essentially, if you are not thinking purely with your stomach when you go out mushroom hunting, you might find that the apparent “moulds” growing across different types of fungi are just as interesting as their hosts.

Red Cracking Bolete (Xerocomellus chrysenteron)

Comments are closed for this post.

Discussion

Great article found as I was searching for information on Bolette Eater as seeing it around at several locations.

Thanks for your kind words Jim, and by all means, I’d be honoured if you quote from this article.

Thank you for a very informative article. I have managed the Eskrigg Nature Reserve on the outskirts of Lockerbie, Dumfriesshire, for the past thirty-three years and this is the first year have come across the ‘Bolete Eater‘.

Visitors to the reserve have also been asking about these ‘strange, smelly structures‘ so I am now able to explain to them what has been going on. I will include an article about Hypomyces chrysospermus in the Reserve’s September Bulletin and would like your permission to quote some of your facts.

Jim

Lovely and knowledgable article with pointers to more information for anyone needing that. Wonderful photo’s I thoroughly enjoyed this article, thank you for sharing.

I see you mention Hypomyces chrysospermus as the “bolete eater” a few times, but then you show pics of Xerocomellus chrysenteron?

Why no discussion on Hypomyces microspermus and the other “bolete eaters”?

Kenny Rupert

17 March, 2023